You never let a serious crisis go to waste. And what I mean by that it’s an opportunity to do things you think you could not do before.

–Rahm Emanuel

Even before the Great Recession, public employee pensions were an easy target. Nationally, there has been a decades-long drumbeat against unions. In Massachusetts, there has been the fanfare and Boston Heraldry of the loopholes and abuse at the state level. But the manufactured crisis of unfunded liabilities is a recent development. There are problems. But a crisis? Not so much. Pioneer Institute to the contrary. What we’re facing is another offensive public support for retirement income, an offensive that began decades ago with attacks on Social Security’s viability, and the ongoing problem of providing health insurance.

It’s not exactly news that state and local pensions are not fully funded. The Commonwealth began to examine state pensions back in the 1970s and started them on the path to full funding. Since then, employee contributions have increased. In 1983, the Pension Reserves Investment Trust (PRIT) was established to invest and manage the state pension funds. “Prior to the establishment of the PRIT fund,” says the MBPC, “the state funded the pension system on a “pay-as-you-go” basis—the state would pay out retirement benefits as employees retired without setting aside the amount of retirement benefits that employees were accruing yearly throughout their employment. This essentially meant that the state was not saving up funds for its future obligations.” It wasn’t until the 1990s that a schedule for funding was adopted.

An unfunded pension liability—the difference between the promised benefit and the assets to pay for it—sounds worse than it is. Nobody wants a liability they can’t pay for. Yet many people carry unfunded liabilities in the form of mortgages, paying as we go, and most of us don’t have the assets to pay off our mortgages all at once. The goal for PRIT and other state retirement trusts, however, is to have enough assets to pay for 100% of future retirements. Full funding will eliminate or alleviate unforeseen problems such as market downturns and increases in the life expectancy of retirees.

Since the Great Recession, most, if not all, pension trusts have taken a hit, but prior to that most of Massachusetts’ retirement funds were on track for full funding by 2030. The vast majority of current pension plan problems are due to the recession, but funding problems can also arise when employees or employers don’t contribute enough to their pensions. In the last 40 years or so, the Commonwealth has addressed the need for increased employee contributions. Teacher contributions to the Massachusetts Teacher Retirement System, for example, increased from 5% prior to 1975 to 11% during the 1990s. Contributions vary for the various state retirement funds. State police pay even more into their retirement than teachers. NOTE: None of us pays into or receives social security.

Nationally, it’s not uncommon for employers in other states to neglect their contributions. Between 1995 and 2005, for example, the City of Chicago shorted the pension trust by 2 billion dollars. The same thing happened in Rhode Island. California has a $73 billion shortfall due to the state’s failure to contribute its share. Many of the fiscal problems with the United States Postal Service are due to the fact that “in 2006, Congress forced the post office to start prefunding its benefits for retiree health care on a schedule designed to reach full funding in 10 years. Now, the Postal Service is supposed to put about $8 billion a year toward retiree health care.” Something that should and could take place over several decades, but requiring the USPS to do so by 2016 is ridiculous.

Massachusetts municipalities may be somewhat slower than states to move away from unfunded pension liabilities. Given that their individual liabilities extend into the millions, that should come as no surprise. It takes decades to fully fund a pension for the first time. And due to tax cuts and decreases in the long-term and the Great Recession in the short-term, state aid has dropped precipitously by 37%. When state aid decreases, municipalities shift their money around to provide essential services. Market crashes after the collapse of the dotcom and housing bubbles have also thrown full funding off schedule. Investment funds are providing below average returns. Fully funding pensions is important, but unlike an ambulance service, no one will die if it takes a few more years to fund them.

Another retirement issue on the horizon is health insurance, but even it is not exactly in crisis. The Commonwealth has been addressing the issue, but it’s also part of the large problem of providing all Americans with health care. Other Post-Employment Benefits, as retiree health insurance is called, will be fixed when the overall health insurance problem is solved. None of this will be good enough for the Beacon Hill Institute, which believes in “limited government,” a government that limits its interests to those who can pay for it.

I don’t know of a mortgage that requires one to earn a 8% raise each year, in order to repay the note.

The 37 municipalities that filed for bankruptcy surely think its a crisis. The retired cop of teacher from Detroit thinks it a crisis. When unions in Salem Ma refused to make healthcare concession, those city workers who were fired, think its a crisis. A family of 4 in Waltham owes $52,000 in unfunded healthcare and pensions, I think that’s a crisis.

The reforms Deval made were a good start, but that’s all it is. More must be done.

More must be done. We need a legal system that holds municipal government to their promises. If we can make sure that a person makes good on their debts to all why can’twe do the same for towns and cities? Sad how many people accept that “bankruptcy” is a legal term that allows stiffing regular people while demanding that the banks hbe fed.

it is necessary to fully fund pension systems. What the post is arguing is that failing to fully fund pension and health care systems does not not necessarily create a fiscal crisis for a public entity.

Detroit has filed for bankruptcy for many reasons, rising pension costs being among them. But not every municipality is in the same boat as Detroit. So using Detroit and other bankrupt municipalities as examples of why public employers and employees must pay more to fully fund their pension systems doesn’t wash. Certainly, attempts to fully fund Detroit’s pension system would only have hastened its backruptcy. As Dickens (I think it was) said, you can’t force people to pay out money they haven’t got.

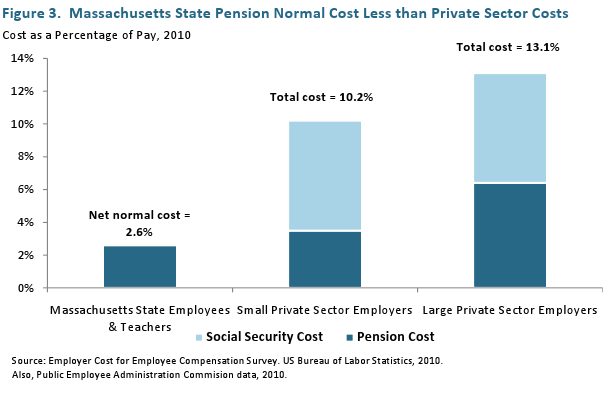

that opponents use to prove their rule. The state pension system is cheaper than private sector benefits: As MBPC writes,

As MBPC writes,

What you cite is not what the State of Michigan discovered, when they put all their workers on 401-K’s. It’s not what San Diego discovered when they did the same analysis of the data.

Pensions by public entities put private employers at a hiring disadvantage, if you think about it. Nobody gets pensions in the private sector, that went out with the hula hoop. And to say pensions save taxpayers money, is just not credible. These states and cities don’t fund their obligations, not b/c they are evil, its b/c they don’t have the money. And to expect 8% return every year on your fund, well you make the case of privatizing social security.

If our 401-K’s drop in value, we are SOOL. However, outside of bankruptcy, the taxpayers backfill pension shortfalls, that’s what is a crisis. I won’t bother with healthcare retiree obligations.

For one thing, most state and local governments are not going bankrupt due to pension obligations nor is there any evidence to suggest that this is going to happen in any more than a very small percentage of cases.

There is nothing wrong with carrying future debt as long as there as an expectation that you will be able to pay. It doesn’t really matter whether or not you “fund” the debt upfront or simply budget for it.

Yes, there are Cites that get into trouble because they have not kept their spending and debt obligations in line with their revenues. Some of this is partly due to bad pension management, but it is not the only reason that Cities, including Detroit, get into trouble.

If you are going to argue that pensions are bad because Detroit is going bankrupt, then you may as well argue that mortgages are bad because some guy in Florida declared bankruptcy when the housing bubble burst.

To you, “cold hard facts” are simply anecdotes that support your already formed opinions, nothing more.

Moody’s lowered Chicago’s bond rating b/c of their pension obligations.

“”The current administration has made efforts to reduce costs and achieve operational efficiencies, but the magnitude of the city’s pension obligations has precluded any meaningful financial improvements,” Moody’s said.”

http://www.chicagobusiness.com/article/20130718/NEWS02/130719803?template=mobile

lower Chicago’s bond rating: they owe billions in pension benefits.

What is it? Your recollections from Fox News?

I’m pretty sure that pension funds have essentially the same interest rates as mortgages. While mortgage rates are currently less than 8%, there were many years when they were much higher.

The comparison is perfectly reasonable.

Does anyone remember if the state ever paid back the millions of dollars that Mike Dukakis borrowed from the state pension fund to balance the Massachusetts budget one year?

Who’s they? The City that mismanaged the pension system for 20 years? The people indicted for corruption? Or the new workers but have no choice but a 401k that won’t help them much?

San Diego isn’t evidence against public employee pensions, it’s a case study in how they shouldn’t be managed.

http://legacy.utsandiego.com/news/metro/pension/pensiontimeline.html