Back in the ’90s when the bottle bill expansion was being considered, I was all for it. However, my graying hair serves as a reminder this isn’t the ’90s anymore. As a staunch liberal, I find myself unable to support Question 2 on the November Massachusetts ballot. Here’s my reasons why:

1. Dated solution

The bottle bill was designed to create a recycling mechanism when no alternatives existed. Now many of us have single stream recycling or pay as you throw programs in the cities/towns where we live. I’m a Brookline resident. We’ve got single stream and I can’t remember the last time I saw someone redeeming cans or bottles at the supermarket. People just eat the 5 cents on their soda and beer containers because it’s easier to do it in their homes than carry containers back to the market. A big part of being liberal is embracing change.

2. Regressive tax

No way around this one. I can afford not to care about 5-10 cents on a container. It’s petty to charge me that money when I’m recycling anyway, but the money is small enough that I don’t feel a pinch. However, those at the bottom of the economic scale are going feel this in their pocketbook. I can rationalize the charge for soda and beer containers as being a bit of a sin tax, but for water or juice? That’s regressive any way you cut it.

3. Recycling disincentive

Lower wage earners and immigrant populations recycle the least, even when they live in places with single stream programs. Expanding the bottle bill would give the people who have to care about reclaiming that money one more reason not to use the municipal recycling program they already don’t use enough.

4. Health

The expanded version actually would make struggling families less likely to make healthy choices in their shopping. It costs more to drink real juice as opposed to sugar water. Even a lot of supposed juices are just sugar water with a splash of juice thrown in and they tend to be the less expensive ones. Anyway, adding cost to the sticker price of healthier choices is going to create fewer people making those healthier choices. That’s bad public policy.

5. Biodegradable containers

This is the one that really baffles me. Yes, we should be recycling beverage containers (including dairy and baby formula, which are excluded from the expansion). However, why aren’t we putting beverages in biodegradable containers? Seriously, any percentage of our plastic containers ending up in landfills or heading out to sea to form a floating garbage mini-continent is a bad percentage. The problem isn’t that we aren’t sufficiently leveraging our bureaucracy, it’s that we need to stop putting beverages in plastic containers. The liberal solution here shouldn’t be to nudge the recycling needle, it should be to meet the crisis head on.

In short, it’s a dated, regressive measure likely with negative unintended consequences and we really should be after much bigger megillahs. To me, it feels like this is an item from some old checklist we really should have updated.

Worth discussing though.

Give a goy willing to learn a hint, please.

That’s how I always said it, because Magilla Gorilla. I’m a goy too. Yet apparently it’s megillah. It’s a big/long/complicated/tedious/cumbersome story, ordeal or thing.

1) Goody for Brookline, but there are still plenty of bottles that end up in the waste stream and roadsides. But yes, let’s increase the deposit so that it is meaningful once more, even to Brooklinites.

2) A deposit may be a nuisance, but it isn’t a tax. Unless you elect not to pay it. (Who does that? Oh yeah, Brookline.)

3) This one so garbled that I can’t reply to it. But some actual evidence would be helpful.

4) This one less garbled, but evidence needed about the magnitude of this supposed effect. By the way, outside of Brookline if you are really hurting you’d buy deposit-free frozen concentrates over bottle juices.

5) There are many reasons why we are not putting beverages in biodegradable containers (starting with that they degrade, think about that). But to the extent that this is feasible, the bottle bill does not discourage it. Make these magic containers deposit free.

1 and 2 betray a Brookline-centric view of the world in which this regulation is just a pain in the neck. It’s more than that.

3-5 come across as afterthought ideas invented to support the gripes of those annoyed by the nuisance. They do not hold economic water and should be recycled. No deposit required.

1)You do realize increasing the deposit to make Joe Average Brookline feel the pinch would price a whole lot of people out of buying beverages at all, right? Anyway, the point is people have another, better (because it involves way more than bottles), more convenient way to recycle.

2) If you’re working 2+ jobs and you’ve got a family and you’re scrambling for everything from transportation to child care to food, redeeming your deposit is a bit more than a nuisance. The hardship on this is going to hit the people who lack both the time and the money for it.

3) It’s not that tricky. We’ve been given 50-60 gallon toters all across the state that collect all our recyclables. Some people don’t use them as much as others – lower income homes, immigrant families, the elderly. Municipalities have been trying to convince those population segments to recycle more and now the expanded bottle bill would actually make it costly for them to put certain items in their toters. That strikes me as counterproductive at best when the larger goal is to maximize what we capture from the solid waste stream.

4) If only more people bought concentrated juice. The reality is soda’s the dirt cheap beverage of choice. Gallup polling shows that poor and non-white folks consume it in higher numbers. Anything that makes the sticker price of soda more attractive against healthier choices is bad policy.

5) Maybe our society could endure without eternal shelf-life.

Responding to your initial five…

1. Yes, Brookline does have single stream. However, Brookline pays to recycle, about $60/ton. Every bottle and can that goes to the grocery store saves Brookline’s budget. And, as it turns out, states with deposit laws have much higher recycling rates. It’s not even close, and the google can help you out here. I’ll write it again: even if there is ubiquitous curbside recycling, the bottle bill results in a higher recycling rate than not having it.

2. It’s not regressive, and it’s not a tax. It’s a fee for not returning the bottles, and it’s entirely voluntary. Calling the nickle fee regressive is like calling a gallon of milk regressive because, as a percentage of income, milk costs more for lower income families. Paying the deposit is optional — it isn’t a tax, and it isn’t regressive.

3. Your claim is that a population doesn’t recycle enough, and if we expand the bottle bill and they start recycling those bottles, that will mean that they care even less about recycling? Does not compute.

4. Juice isn’t particularly healthy — pediatricians and dentists will tell you that. Same goes for sports drinks, Snapple, and the rest. Water is healthy, and it comes right out of the tap, no single serve bottle necessary. Milk is healthy (at least for kids), and there would still be no deposit there. And frankly, you’ve provided no evidence that the consumption patters are altered by the deposit — there’s over 30 years of data out there, if your claim is true, back it up!

5. Biodegradable containers are a fine idea. I’m not aware of one that exists at the commercial level, but cool! Let’s do it. In the mean time, let’s do this.

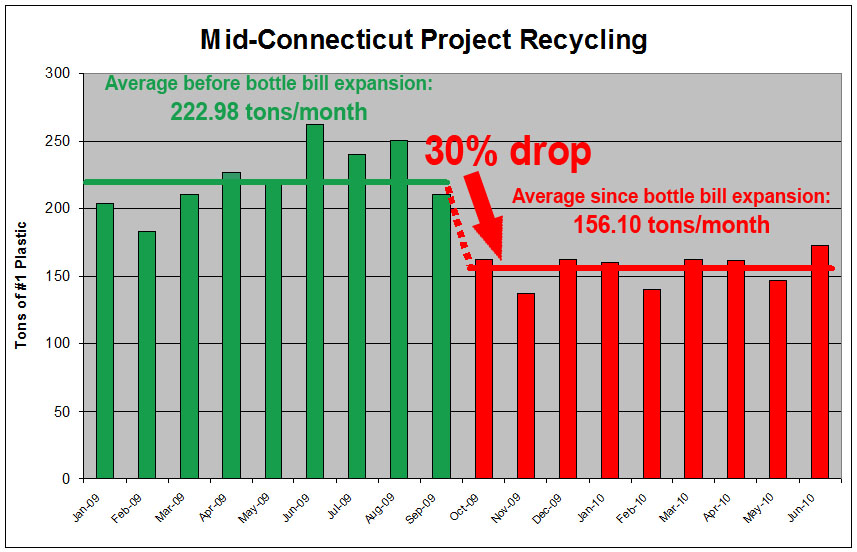

Connecticut expanded it’s bottle bill in 2009. Here’s what happened:

![]()

Connecticut has curbside recycling too. The fact of the matter is that expanding the bottle bill will result in more recycling. It will result in less litter. It will save city and town budgets, for cost of recycling, collection, and litter mitigation. Vote Yes on 2.

It belongs under

Connecticut expanded it’s bottle bill in 2009. Here’s what happened:

What is the X-axis? Tons of plastic where? In the non-recycled waste stream? How can they measure the plastic content in that? Is that the number of tons in their single-stream recycling program?

While I largely agree with you, it is not the case that having to return bottles to get your deposit back is exactly free. You need to actually carry the bottles back to the store and spend time feeding them to a machine to get your money back. That takes time and effort and would be especially annoying if you don’t have a car. Yes, the empty bottles are light, but they are also bulky and if you buy products from multiple stores, you may have to make sure to take them back to the right one. This is why many people like myself don’t bother to return bottles and simply put them in the recycling bin. Someone with a tight budget and who is working two jobs will have to choose between taking the extra time and effort and losing the fee.

So it isn’t really honest to say that this will not have a modest regressive cost to those at the low end of the economic spectrum. Perhaps it is a low cost, but it is a cost nevertheless.

[And to be clear, I do support the expanded bottle bill.]

For anyone in an economic position where the new deposit on water bottles matters, buying bottled water is just plain stupid.

Water from the tap is free and perfectly safe. Bottled water is infinitely more expensive that tap water (because tap water is free) — worrying about an additional deposit is meaningless.

While tap water is mostly safe, especially in the Boston area, I don’t know if that is universally true and there are still buildings that contain lead piping or have rust or other deposits that make the water taste bad. Of course you can buy a filter, but that also costs money. It is also more convenient to simply buy bottled water rather than deal with filling and cleaning water bottles, so while buying bottled water is indeed wasteful it really isn’t all that surprising that people continue to do it.

Furthermore, we aren’t just talking about bottled water in any case.

In any case, I don’t think I was saying that the cost would be prohibitive. Just that we shouldn’t pretend that it is zero, because it is not.

And that’s just the start.

Tap water is controlled by the EPA with standards that are much more strict that the FDA which controls bottled water.

Bottled water is a product of marketing. The Big Three bottlers saw their market shares dropping as people began to drink less Coke, Pepsi, Snapple, they decided to market “water” as a way to lift sales.

Yes, Americans are that gullible.

The other was, no deposit.

Sorry to burst anyone’s bubble, but Poland Springs doesn’t exactly have anyone taking buckets into the Poland Spring and the pouring water into a bottle.

They were just one of the first companies that figured out if you put a stream of water and a deer on the bottle and market the hell out of that, you could hoodwink millions of people into thinking it’s “fresher” or “safer” to the point where those millions of people will pay more for one single 20 ounce bottle of water than they’d pay to drink all the water from their tap for an entire year. Just like they could they’ve been doing their entire lives.

If companies used honest marketing and showed water coming out of the tap on giant assembly lines, suddenly the demand for something people already have virtually free in their own freaking home would be almost nil.

Tap water is safer, better and virtually free to drink. It just doesn’t get marketed with the pretty Maine spring, green trees and deer.

I thought marketing was required to be truthful.

There is no law banning misleading ads.

There is no law banning Poland Springs from marketing their drinks with images of Maine springs, forests and deer.

And there are plenty of laws that are bent or outright broken in every day — you have this thing where you think that just because laws are on the books, it’s mission accomplished and they are never broken or taken advantage of.

All bottled water is just water that comes out of the same places or types of places that all drinkable water comes from.

The rest is just marketing.

…there were truth in advertising and truth in labeling laws. If they aren’t being followed the appropriate agencies need to address that.

that makes it exceptionally easy to mislead just about anyone?

Christopher… this is just a ridiculously naive view of the world you have.

Laws aren’t written like bedtime stories of how the world is supposed to work… they’re largely written by lobbyists.

Have you ever heard of the expression “lies, damned lies and statistics?” Something can be true and completely misleading at the same time. Marketing relies on that. No laws are broken in doing it. It’s still misleading, dishonest and entirely par for the course.

If they advertise that they are selling you spring water, and it is not in fact spring water that’s not misleading – it’s an outright lie.

Is that “spring water” is anything different, nevermind better, than the tap. As spring water was defined here, it applies to the majority of fresh water sources in the world.

Spring water in today’s world is a marketing term meant to mislead people into thinking they are getting something better or fresher than what the vast majority can get out of their faucets in this country.

which was that it is municipal tap water

I lived for a year in North Andover, which was the last community in the state to pump untreated lake water into residences. It came from Lake Cochichewic, which had recently had a flurry of McMansion building on its shore. Early that summer, the water in the toilet turned a lovely shade of bright green, because of the algae bloom fostered by the McMansions’ lawn care chemicals. Later in the summer, the algae died, and the green turned to a less-lovely brown. In the early winter, residents learned from The Globe that we should boil all our drinking water, because of a Giardia infestation in the lake. The town installed generator-powered chlorine injection pumps at scattered places in town as a temporary measure. Later they built an actual water-treatment plant, but I had moved on by then. My point is that for that year, at least, bottled water was a better, safer alternative to what the town was providing.

Poland Springs water is, in fact, spring water, as defined by the FDA. Many municipal water supplies are not spring water – for instance, MWRA and the town of North Andover’s water supplies are pumped from surface reservoirs, and Burlington’s is from wellfields, and Lowell’s is sucked out of the Merrimack River. My remarks to the effect that spring water is not necessarily isolated from surface water should not be taken to mean that spring water is always the same as surface water (or tap water). I’m not saying that, and it’s not true. It is true that the aquifers that supply springs are not immune to contamination, as many unfortunate people who live in areas where fracking is done have found. That’s not happening in Maine, but it’s not inconceivable that some other source could contaminate one or more of PS’s springs. I would hope they’d be on top of that and stop using any spring that showed a taint. As ryepower points out, though, PS is not required to test with the same rigor as municipal water supplies. They may do so, and it would be smart of them to do so.

Filed in Hartford CT

There are laws regulating truth in advertising.

The law says that product labeled “spring water” has to come from underground. Poland Springs water is not tap water. About 1/3 of it is from springs in the town of Poland Spring (the original Poland Spring apparently went dry some time ago.) The other 2/3 are from other springs in Maine.

Note that there’s a word for “a borehole that taps into the underground source.” The word is well. Wells and springs are not necessarily isolated to any degree from surface water. As others have said, muni water supplies are far more regulated and scrutinized than bottled water is. I don’t think Poland Springs sells tainted water, and I do like its taste, but if there were some kind of contamination in the office bubbler of PS water, how would I know?

The water in coming out of your faucet and the water in your Poland Springs bottle comes from the same place. What do you think, the wells and springs of Maine are magical? The vast majority of the water in the world comes under the very same classification as what you described. Well water is far more common than any other source.

I never said Poland Springs sells tainted water. There’s nothing wrong with its taste. In fact, it tastes every bit as good as the water that comes out of my faucet.

As for contamination — that can happen with any water bottle. It’s rare, but happens and if you leave the bottle alone for a long time or leave it in the sun, it’s more likely to be contaminated.

Bottled water is also regulated by the FDA, which has no teeth and is funded by the very industries it regulates.

Municipal water is regulated by a different federal agency, which has much stricter standards. Its water is constantly tested.

You’re welcome.

I don’t get why people without much money choose to waste what little they have.

1. It’s far more strictly regulated, tested and looked after.

2. Drinking from plastic water bottles, particularly those left in the sun, is something scientists are beginning to understand is not good.

3. Bacteria can actually form in bottled water, even unopened ones, if given enough time.

Bottled water should be something people use for emergencies, rotating enough in their house to have a few days supply in case of a disruption in the water supply.

According to the FDA:

That link is to the FDA’s page addressing everything to do with bottled water. The definition there for spring water is a little different from the one I quoted earlier, so I withdraw my comment about wells. Even so, it’s entirely possible for a spring to be contaminated.

It’s easy to jump to the conclusion that anybody who would buy bottled water when it’s free from the tap is stupid. However, last I checked your tap doesn’t follow you around outside of your home.

Now, you could fill up a metal or squeegee bottle and bring tap water with you when you’re out for the day. I do that frequently. Yet there is a certain convenience in having your travel water in a disposable container, particularly if you’ve got a family. You can get a case of water bottles at the supermarket for not much more than the cost of a single water bottle at a convenience store. It’ll cost you 10-15 cents a bottle if you stay off name brands and you don’t have to keep track of everyone’s permanent water bottle. So if you’re out walking or driving around for an extended period of time, or if you’re having a picnic or attending a sporting event, it’s a fairly cost effective way to stay hydrated.

It does actually offer a rational, lower cost alternative to people who are looking to save money in those situations.

When you “stay off name brands”, you’re buying water that somebody else put in a bottle. The “convenience” you refer to is more commonly called “litter”. I guess people should skip the lunchboxes and encourage their kids to just throw a paper bag on the grass when they’ve finished their lunch, right?

There is nothing “thrifty” about buying a “disposable” container, paying somebody to fill it with water, and then expecting somebody else again to collect it from wherever a person decided it was “convenient” to walk away from it.

Buying bottled water is stupid. Expecting other people to serve your “convenience” is boorish.

Buying one bottle of water at CVS costs more than all the water you could drink from a tap for an entire year.

Which lobbyist company do you work for?

Muni water is not free. I pay a couple hundred dollars a year for the town’s water. Your landlord probably pays even more. That you don’t pay it directly doesn’t mean it doesn’t cost anything.

For a better perspective, consider: I used to buy gallons of Market Basket water at about $0.50 a gallon, because the tap water is kind of nasty here.. Say conservatively 5 gallons a week, or 20 a month. So $10 a month. Buying small bottles would cost much more, even if they were also store brand. Then I put in an under-the-sink filter. With the first filter cartridge, that cost about $75. Each cartridge lasts about 3 months and costs about $10. The thing makes great-tasting, chemical- and bug-free water, and paid for itself in less than a year. If I’d been buying designer water, it would have redeemed itself even faster. People getting MWRA water don’t need anything like this,because the Authority does all that for them, but it’s not free.

The water that you drink is virtually free, since it’s such a small portion of the water that you use that it’s less than a rounding error on your bill.

Showers, baths, laundry, dishes, lawns… that adds up. Turning on the faucet for 5 seconds to fill a glass of water? Not so much.

That said, I don’t think buying the gallons is a bad thing. What I’ve said isn’t an indictment on you and I certainly haven’t called for bottled water to be banned.

It has its purposes — and far fewer hindrances. There’s far less plastic being used that way and no one takes that with them on the road — so it doesn’t end up litter. You’re still spending much more than you would for tap water, but if your town has a poor source, then I wouldn’t begrudge you for making that decision. Heck, I’ve argued on this thread that people should be buying gallons of water (for emergency rations), but also regularly cycling through them (because you don’t want to those gallons sitting around forever — bacteria can grow in them after a long time) – which would mean *gasp* people should drink them.

I think the small bottles at the stores are a bad, really dumb idea in that they’re incredibly costly and wasteful — but note that I’m not saying they should be banned.

I think they should be hit with the same nickel deposit that soda is. That’s all. Nothing “way overboard” about that.

because it is not a tax. It’s an entirely voluntary fee.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regressive_tax

By definition, a user fee is not regressive. The bottle deposit is an optional user fee, not a tax.

As for the “no car” argument — cans and bottles weigh a hell of a lot more full than empty. If the person can get them from the store to the home without a car, he or she can sure get the empties back to that same store. There’s no significant extra time — people buy groceries on a regular basis, and the bottle return is at the same location.

It’s not regressive (by definition), and the additional time required is marginal.

Is the thing we call the cigarette tax also an entirely voluntary fee?

If we were allowed to redeem our cigarette stubs for a full refund of the tax.

Buttle bill. I’m game.

No, it is not a tax. Nevertheless it is indeed regressive in the same sense that a regressive tax would be. The usage of the word “regressive” is not strictly relegated to taxes.

And it is just plain false to claim it is an “optional” fee. What is optional about it? You have to pay it. You just have the option of getting it back if and when you return the bottle.

So yes it is indeed regressive, at least a little bit.

BTW, I sure hope that all the people who are saying that returning bottles is no burden at all are speaking from personal experience of always returning all their bottles.

It is just refundable if you go through all of the necessary machinations, which less than all people do, and the government keeps the leftover money. It is just a complicated tax.

It hasn’t even been that long since Paul Ryan tried to use hikes in “user fees” in order to “reduce taxes.” But, spluttered the Democrats, the user fees pay the same costs that the taxes did, but are more regressive. That’s terrible! Not “regressive” in the sense of an income tax, since this is not an income tax, but regressive in the sense that the government is making money, and the money is likely coming disproportionately from the least wealthy citizens.

Of course this is a tax. And apparently a tax that is designed not to make a lot of money, but rather to make some money while causing certain consumer waste to be re-directed from Recycling Stream A to Recycling Stream B.

They are an, “If i I’m not using it, I’m not paying for it” method for paying for services that gov’ts can’t avoid providing. They are also a way for politicians to raise revenues while claiming not to have raised taxes, Mitt Romney can you hear me. This deposit is just an incentive to facilitate the recycling of a raw material, keep our communities clean of litter, and save the cost of filling our expensive landfills with otherwise reusable material. If consumers return the empty bottles the next time they shop, not a special trip, they will get their money back. Too many people don’t bother with curbside recycling in their communities to drop this.

This isn’t the make or break point with me, but for me this is just so much bullshit peddled by politicians and their devoted fans– principally because it is one of those principled positions that, when the circumstances change a little bit, is discarded and forgotten so that its opposite can be embraced, say, the next time a Republican Congress wants to cut taxes and increase user fees.

It is a little like defending the filibuster as a Bastion of Democratic Virtue by the political minority, who assail it as an anti-democratic cancer when they happen to be in the majority.

The old position is entirely erased from memory. We have always been at war with Eastasia.

Anyway, for me this is not really the make-or-break issue for me, as I really do not care all that much if the overall tax burden is regressive or progressive. But sheesh, don’t spew BS and expect that it enhances the credibility of the position.

That has more principally principled principals than intended!

You can just dismiss them in so many ways, then walk away declaring victory. Yes, it’s semantics, and it has been used by politicians to defend or promote actions, one way or the other.

1) And, as undercenter noted, our municipal recycling costs won’t turn to profits until we up the tonnage coming out of our toters, which is a major reason why the toters are so big. Taking solid waste out of our single stream recycling via an expanded bottle may be pennywise today, but it is dollar foolish in the long run.

2) Only in a world where everyone can and does adhere perfectly to the bottle bill is it not regressive. On top of that, the working poor do not have the luxury of free time. The argument that this particular straw won’t be breaking any camels’ backs doesn’t change the fact that there are those to whom this will be burdensome.

3) In your response to #1, you accidentally tripped over why this matters. The battle over the long haul is to get everyone toters and have them fill the things. The expanded bottle bill will drive behavior away from using the toters.

4) Nowhere did I say people should drink juice exclusively. You really shouldn’t drink anything exclusively, including water. However, when you’re drinking something other than water then actual juice is a far better choice than sugar water. As for the alteration of the consumption patterns, the patterns are already so bad that it would be foolish to pursue anything (like adding to the sticker price of healthier choices) that would push the needle in the other direction.

5) Fair points, but I still say that’s a narrow perspective on the larger issue. I don’t want to do something. I want to get somewhere better than where the expanded bottle bill might take us (e.g. somewhere way ahead of CT).

1. Paper is sometimes profitable, sometimes not. Heavy metals are profitable. Plastic? Nope, and there’s no reason to think that it will be. Glass? I don’t remember. Bottom line, if we put more material in our recycle bin (instead of Stop & Shop’s bin), the Town costs will go up. Pretending otherwise is grasping at theories that don’t match reality.

If you’re talking about our (Brookline) costs, it went like this. The tipping costs for trash at the time we went to single stream were $82/ton. Recycling was about $60/ton. For every ton that Brookline residents recycled instead of threw in the trash, the Town would save $22. When we went out to bid for recycling, it turned out that (a) the cost of a ~60 gallon toter was trivially more than a 35 gallon, and (b) subcontracting the service out was cheaper than doing it in-house. Because of the trash-recycling cost differential, the decision was to oversize the recycling bin because the added cost was low, and the cost of trash-instead-of-recyling was high. Brookline has made a smaller recycling toter available for those who request it — commonly because the resident is a senior and can’t physically handle the larger size, because the resident’s preferred storage location can’t fit the larger toter, or because the resident lives on a hill and the larger toter is too heavy. I know all of this because I served on one of Brookline’s pay as you throw committees.

2. That’s not how regressivity works. Because the fee is strictly optional for all users, it can’t be called regressive. But if you’re worried about how much each user will voluntarily pay into the system, do you have any evidence that rich people are just as likely to bring back their bottles as poor people? Do you have any evidence that poor people buy more or fewer bottles than rich people? My bet is that you don’t have any evidence for either, so your claim that it’s regressive, in addition to not making sense because of the optionality of the fee, lacks any proof. I’d add that a number of people in Brookline make a “living” collecting the bottles. They’re likely quite poor, and for them the bottles are a revenue stream, not a cost — which will make your regressivity chart do flips.

3. “The battle over the long haul is to get everyone toters and have them fill the things.”

No. The battle over the long haul is reduce, reuse, recycle. To minimize what goes to the landfill/incinerator. Bottle deposit laws have existed for 35+ years, and over the entire time, across the dozen or so states that have deposit laws, the evidence is always the same. Recycling rates are higher where there are bottle bills.

“The expanded bottle bill will drive behavior away from using the toters.”

Why? People no longer will have paper to recycle? Empty baked bean tin cans? Milk containers?

4. Again, there’s no evidence that the five cent deposit on the $0.50 – $1.00 per container of beverage has any influence on purchasing. Absolutely none. If you’ve got any, please provide it.

5. If you want to get way ahead of Connecticut, here’s how you do it: (you won’t like this)

a. Make the deposit 10 cents. Michigan has the highest beverage container recycling rates in the country — and they’ve been 10 cents for years.

b. Then, write in the law that the deposit price is tied to inflation, rounded to the nearest nickel.

c. Expand the bill to water, tea, sports drinks.

d. Expand the bill to wine and liquor bottles (25 cents? 50 cents? It’s 15 cents in ME)

e. Require broader acceptance. If Trader Joes sells Heineken beer, it has to accept all Heineken beer bottles, even if the UPC symbols don’t match. TJ (for example) is notorious for requiring that its products have a different UPC than other stores, so when you go back with Heineken bottles purchased from TJs and from the local packie, half get rejected. That’s crazy. Accept ’em all.

Massachusetts has higher recycling rates for non bottles, particularly because we have a high recycling rate for construction and demolition (C&D) waste. But we’re behind CT on beverage containers, precisely because CT has a broader bottle deposit bill than MA.

It’s the conception of a mind who views the world of trash collection through an exclusively bottle bill lens. ‘m not even opposed to any particular part of it, just that it’s exceedingly small-bore. Seriously, it’s deck chairs on the Titanic type stuff.

You clearly have no vision of how to turn our current recycling cost center into a profit center. It is what is and apparently to your thinking it will never change, so bottle bill expansion. You’ve convinced me. No on 2 so that people like you will be forced to buy a clue.

n/t

Edited version.

To you?

My my my. WHAT is the world coming to?

I didn’t complain about anything at all.

I wrote a shorter version of drinkeo’s post, which is a blog meme I first saw on Atrios’s blog, in which someone makes a short description of a bigger post. It’s often used as satire, which was what I attempted to pull off.

Given the disjointed argument one has to make to both claim something is 1) pathetic and that 2) he agrees with that something completely, I think my attempt at humor was warranted.

As for my comments that you quoted — if you bothered to link to them, others would have been able to make their own judgments with context. With that context, i think most would agree that they were warranted.

1. I am trying to do a little bit of research on this, but it is hard on this subject to find much beyond the PIRG propaganda on the one hand, and beverage distributors on the other. It has long been my understanding that the problem with plastics recycling is (i) that unlike metals, the quality decreases on each cycle; and (ii) it is hard to sell because the seller must establish a readiy and reliable supply of a certain quality material, and that kind of stability was hard to establish at first. So things started small, and new materials were only added to the “single stream” as outlets were developed.

It sure seems to me that, now that these markets for recycled materials have been so painstakingly established, that programs like this, which divert the same supply of material to a different outlet, could undo all of that effort. So, a significant incremental improvement to a fraction of the overall stream, potentially at significant cost to the ability to recycle the rest of the stream.

The alarm bell went off in my head on this when I saw someone on the other thread say “I don’t care about the success of the recycling industry! I just want to reduce litter!”

2. Absent evidence to the contrary, I don’t think one can assume that redemption rates vary by wealth. Participation is a time and convenience thing, and that cuts all over the place. It is likely the case that everyone, on average, pays $X into deposits, receives less than $X in redemptions, and that the value of this difference is a greater portion of the disposable income of the poor than of the rich. It is, in essence, a redeemable grocery tax, and taxes on groceries are about as regressive as taxes get.

3. I am going to disagree here, as a bottle bill has exactly zip to do with “reduce” or “reuse.” It is all about recycling. And I have to agree with drikeo that the object there is to get as much as possible out of the trash and into the recycling bin.

4. I am not interested in tax policies designed to influence what beverage someone chooses to drink.

What makes you think that they go to a different outlet? The recyclables collected by municipalities get sorted, and then go on to processing. The recyclables collected by grocers get sorted, and then go on to processing. What makes you think that there is any diversion (other than diversion from landfill to recycling, because bottle bill’d bottles have higher recycling rates than non bottle bill’d bottles)?

I absolutely disagree. That’s like arguing that rich people and poor people clip grocery questions equally. They certainly don’t. I don’t know the extent to which poor people clip more coupons (or redeem a higher percentage of bottles), but it’s obvious to me that there is a difference along the spectrum if we look in aggregate (anecdotes will vary of course).

Oh, absolutely. But the bottle bill is a piece of a larger issue: the creation and handling of solid waste. Within that context, the three Rs exist. For the specific tool of bottle bill, it goes after the third R. Safe, clean drinking water, as an example, goes after the first R, because if people drink tap water they reduce their consumption of bottled water (and, hence, the bottles).

1. The point is not to make “Joe Average Brookline” feel a pinch. [I can’t imagine how the average Brooklniner (median income $91,112) would even notice a nickel or dime deposit on his average bottle of water, let alone feel a “pinch.”] The point is to get somebody to pick up the damned bottles and recycle them.

2. There is no “hardship” involved in redeeming beverage containers. They weigh a tiny fraction of what they did when full, take up the same space, and are redeemed at the same place they were purchased – a place that the buyer is almost certainly going back to anyway. If you haven’t seen people returning bottles, it’s probably because the markets have moved the return facilities out of the retail space, into a separate space that you don’t go to, because you don’t redeem bottles.

3. “We” have not been given any such equipment across the state. You may have been given a gigantic recycling bin, and there may be other scattered communities that have given them out, but I haven’t got one. Many thousands of people who live in apartments have no recycling at all, unless they cart their stuff to a recycling facility themselves. Now there’s something approaching a hardship. Bottle deposits actually do address a part of that problem. Your assumption that everyone already has the same recycling services that you have does not.

4. People make bad choices. Do poor people buy a lot of bottled water? If they do, their more sensible and economic choice is to drink tap water, which in the MWRA-served area is as good as, if not better than any bottled water. As for juice, eating fruit is far more healthy than drinking fruit juice. If a bottle deposit has such a large economic impact, it would seem to encourage juice-drinkers to eat more fruit, no?

5. Maybe our society could do without buying bottled beverages entirely. I do. All the complaints you’ve made about the burdens of the deposit ignore the facts that:

A. All of the deposit burden falls on the people who buy bottled beverages as it should. The current exemptions result in everyone paying to clean up after the people who don’t recycle their bottles, even those of us who don’t buy them.

B. Almost no one has to buy bottled beverages.

My beef is not with Brookline, which I think of as a well-run community with a high level of civic engagement.

I do object, however, to people who generalize from their own narrow experience. Everyone does not live in Brookline. Furthermore, even Brooline would benefit from expanding the bottle bill.

..with your observation under No. 1 … to a point. Yes, the main point here is to get somebody to pick up the damned bottles and recycle them, but the overarching goal is to nurture a recycling industry that ultimately becomes self-sustaining and (I know this sounds like heresy) profitable. Greater volume is needed to create demand for recycled materials and the requisite investment in order to grow the industry. And the best, most efficient means of accomplishing that, as I pointed out in a prior thread, is by emphasizing municipal curbside programs – mandating them where they don’t exist, expanding them and making them more user-friendly where they do exist.

Say what you will, the redemption option is NOT the best or most efficient approach in this regard. Granted, the bottle bill absolutely improves the litter equation, there’s no denying that. But litter can be addressed in other ways. Our primary focus should be adjusting public policy to assist an industry (just like we’ve done with solar or wind power) that provides consumer incentives to recycle a wider and wider spectrum of materials, then creates for-profit markets for those materials. Otherwise, all we’ve got is another bureaucratic solution to coerce desirable behavior.

I think voting against this would also set efforts in that area back, by making it seem like the voters rejected a tax and an environmental initiative as too costly. We can build on this bill by making better bills in the future.

That is how progress moves forward on these issues. Indexing the gas tax is a regressive way to raise transit revenue to some extent, but, it is also the best way to lay a foundation to fund future transit and infrastructure investments and encourage fuel consumption. Obviously, a true carbon tax with rebate checks sent to working families is the best public policy-but in this climate it ain’t gonna pass and it definitely won’t pass if the indexed gas tax fails at the polls.

An expanded bottle bill could be part of a more systematic approach to recycling. However, what’s the rest of the system? Because that’s the part that matters most. That would require leadership and neither Coakley nor Baker seem even vaguely focused on this issue.

Using this to build upon is certainly the best argument for it, along with making pols skittish to effect other environmental reforms that may cost money. I find it unfortunate that environmental groups have made this their public step forward. It really is terrible strategy. Though the inertia argument also might apply if it passes: we expanded the bottle bill, so we’re done, right?

I’m glad you asked. I wish you would have asked before pooh-poohing the bottle bill.

Massachusetts has one of (if not the) highest rates of construction and demolition (C&D) recycling.

Massachusetts is in the process of requiring large food service establishments (really large: think the convention center large) to compost food waste. Once the industry pops up to support the industrial processing, the threshold will be reduced to smaller establishments (think university cafeterias). Of course, cities and towns will then be able to establish municipal collection of food scrap waste so it can be composted rather than landfilled.

Massachusetts has programs to encourage pay as you throw (PAYT) for communities. The idea of PAYT is, through a variety of different available mechanisms, those who create more trash pay more. Some towns have a dump where you pay to toss. Others use bags. Others have hybrid systems. In any case, the studies are clear: if you pay more when you have to throw out more trash, you create less trash. Maybe you compost more. Maybe you recycle more. Maybe you don’t buy junky stuff any more. For whatever the reason, PAYT reduces trash — and the Commonwealth is actively providing both guidance and subsidies to cities and towns for converting. Brookline is in the middle of this process right now!

I’m sure there are more examples — MSW isn’t my area of expertise.

Is there a long way to go? Yip. Are other nations leading on this? Yip. Is MA well ahead of most states, and yet still striving to move even further toward reducing our solid waste? Absolutely.

And thanks for summarizing it so well. The bottle bill expansion is pushing the margins and not addressing the larger picture. As a liberal I want to use the tools we have in the 2010s to go after that greater recycling volume. Reaching back to the 1970s strikes me as a conservative, almost fundamentalist approach: THIS is the way we do it. Well, it’s the way we’ve done it, but it’s not anywhere near as effective as we should want it to be so why don’t so something better?

You keep saying that the deposit law is an old approach, and we should “use the tools we have in the 2010s to go after that greater recycling volume.” What are these 21st-century tools? What has changed so much that there are now approaches to recycling that work better than deposits, and what, exactly are those approaches? So far, you haven’t told us.

You also continuously ignore the data that stomv presents, showing that deposits correlate to higher recycling rates, rather than reducing recycling. You may or may not be liberal, but your arguments are not different from the corporate opponents of the ballot question.

What I see is that it increases the rate of recycling of a portion of the overall stream of potentially recycled material. That doesn’t necessarily translate to higher recycling rates. It might, but I don’t know. If it incrementally increases the recycling of plastic bottles, but decreases the recycling rate of other stuff, I am not sure that it is such a super-dooper idea.

What, do you think that people who live in bottle bill states recycle more glass and plastic, but then go ahead and recycle less cardboard because, you know, for some reason? What possible reason could a population have for reducing the recycling rate of other materials because they’re recycling more Coke cans?

The single greatest difficulty in recycling, for decades, has been finding markets for recycled materials. Potential buyer says, “Gee I might be able to use recycled material X in my business, but I must be able to be confident that I can get X quantity of Y material of no less than Z quality, delivered every W days, without exception. Otherwise, I miss payroll and no longer have a business.” When the stream is small, new, and unsteady, the incentive is to say, “no thanks, I’ll just use new material.”

This is not unlike the alternative fuels problem of today: It is tempting to buy an alternative fuel car, but risky because there are so few places to fuel it. But there is no place to fuel it because not enough people use the alternative fuel.

So, over the last 25 years, a recycling industry has grown up. While plastics are still not profitable for the processor, I do believe that the cost has declined significantly over that time. Why? Because as recycling programs have improved, the rate of supply and quality has become more certain, so that there is a better market.

My concern is that this program will divert a significant chunk of the stream away from the existing markets that have been developed over the last 25 years, disrupting them. That could easily result in an increase in the cost of recycling the remainder of the plastics stream. So, yay, instead of recycling 100 tons of plastics at $60/ton, town reduces its stream to 75 tons. But, whoops, those 75 tons now cost $90/ton to recycle, so either the town’s costs goes up, or the town drops the remaining plastics from its program and directs residents just to put those items in the trash.

That is why I would like to see what the existing recycling industry says about an expanded bottle bill. It might be that they say– “It is so hard to do anything useful with this stuff that the removal of it from our hands would be just great.” Unfortunately, the only things I have found thus far are from PIRG or the bevarage industry, neither of which are at all trustworthy.

The bottles that are collected under the deposit law — where do you think they go, the ether? They’re recycled, side by side, with the bottles collected curbside. The industrial plant gets it’s supply of empty bottles from both bottle bill inputs and city/town inputs.

Every bottle that would have been recycled curbside but is now recycled under the bottle bill means one fewer bottle coming into the industrial recycling facility’s loading dock 1, and one more bottle coming into loading dock 2.

Every bottle that would have gone into trash that now gets redeemed under the deposit bill — because every rigorous study of empirical data shows that recycling goes up with the bottle bill — also comes into loading dock 2.

The aggregate impact of an expanded bottle bill on the recycling industry is more recycled bottles — driving economies of scale up, and hence, cost downward.

Your concern doesn’t make rational sense. Curbside collection of recycling is cheaper if fewer items are put on the curb (because more were redeemed). The total tons of plastic being recycled increases with the bottle bill, because total plastic recycling increases — driving down costs due to economies of scale.

Where will this program divert the significant chunk TO? Where do you think returned deposit bottles wind up? As stomv has said, the returned deposit bottles go right into the same recycling stream as the ones in curbside bins. In fact, the deposit system actually performs part of the recovery process, at least some of the time. The redemption machines at my local Market Basket chew the plastic bottles up into little pieces. This saves a huge amount of space at the store, on the truck, and at the recycling facility.

As for your not finding a recycling industry position on expanded bottle deposits, how about this, from the Canadian Plastics Industry Association?

Let’s go over your arguments.

#1 ignores the facts. Vastly more bottles covered by deposits are recycled than those without it — particularly since so many bottles are consumed away from the home, where recycling barrels are almost nonexistent. Without the deposit, bottles end up in the trash or as litter with no incentive for anyone to pick it up.

That’s to say nothing about the fact that very few towns have the robust recycling policies of Brookline.

#2 is a strawman. Bottle deposit policies are not taxes and don’t have to cost anyone a single cent. Given that over 70% of bottles covered by deposits are recycled, compared to half that among bottles that aren’t, it’s pretty clear that the number of those who redeem their deposits is robust.

#3 lacks any kind of evidence and, quite frankly, makes little to no logical sense.

#4 is completely bogus. In reality, bottled water already costs as much or more than soda in almost all circumstances, with or without the deposit. Go to any CVS, vending machine or convenient store near you. Deposits have almost no bearing on cost.

#5 is a complete strawman as well, as it has absolutely, positively nothing to do with the argument at hand… and takes up a completely different and unrelated-to-the-ballot argument instead. It’s wonderful that you’re against the concept of bottled beverages sold at stores to begin with, but that’s not what’s on the ballot and has no bearing on the decisions voters will be confronted with in November.

is a scam. Don’t want to pay a deposit? Here’s a pro tip: buy a PBA free container for a few bucks and voila, get your water virtually free almost anywhere.

My wife and I went on a 20 mile bike ride though the Charles River basins in Norfolk, Medfield area and lost count of how many discarded plastic water bottles were alongside the road.

So while “90% of Massachusetts residents have access to recycling”, clearly, that’s not working.

in his FY ’15 budget submitted to the Legislature last January. The administration estimated that this would bring an additional $24.2 million in additional revenue to the state. The Legislature appears to have rejected the idea. Does anyone know why? Did the Legislature buy the regressive tax argument?

If one lives in a place where recycling is less convenient, there are people who pick up bottles.

One thing you hear people say is “The guy driving around picking up cans is the richest guy in the neighborhood.” Well, where I used to live, not so much.

I support the bottle bill, because it’s good that we have a mechanism that forces recycling. But now that recycling is more or less institutionalized, I’m open to arguments about getting rid of it, and I have mixed feelings about expanding it.

Brookline and Somerville each have very convenient recycling, and each has people who pick up bottles.

Those people are not wealthy. Collecting higher deposits from consumers and raising the pay of those who pick the bottles is NOT regressive.

Raising the pay of people who pick up the bottles?

Thank you for pinpointing my discomfort. How about we find them better jobs?

It’s not a goal, it is a side effect. That the side effect has a positive impact on a small subset of the very poor is a good thing, not a bad thing.

I think our modern day gleaners are noble, just as, I suspect, Jean-François Millet felt that the three peasant women were by surviving on society’s waste. I too want better jobs for the poor — I just don’t see how the side effect of gleaners making more money is an argument against.

I’m probably going to vote for it since it apparently works in the litter-reduction department, but otherwise I have to say I am very sympathetic to the arguments made in this diary.

when I walk my dogs. One time, I counted 15 vodka bottles on my two-mile walk. I’m not saying people wouldn’t throw them out their car windows still, but someone who wasn’t walking two dogs might stop to pick them up.

We still have community organizations that collect the bottles and redeem them to raise money too.

The diarist sounds as if s/he has absorbed the industry’s talking points, which are, to say the least, self-interested.

is terrifying, but not for any reasons related to recycling.

along one street. It’s a long street, but I was perplexed. I’m used to finding empty nips and beer cans. But these were quart bottles!

If I were going by who’s standing on which side of the issue, I’m voting for the bottle bill. There’s a healthy number of people I flat out don’t trust/don’t like on the against side. However, I’m flat out unconvinced this is good long-term policy.

policy. But I’d listen to MassPirg rather than the industry. I don’t think they’re pushing the bill for no reason. The website for the proponents includes the following reasons:

I hang to my redeemables and not throw them away. My high school has been doing better at recycling plastic, but everyday I have kids come in with water bottles and soda cans that I pick out of the trash. Curbside may eventually solve everything, but I don’t think we are there yet.

he or she works for the industry and could possible be paid for being here now.

Litter is to recycling as weather is to climate. One is a localized condition, the other is a system.

…improving litter conditions is unlikely to deliver systematic recycling solutions, but creating systematic recycling solutions would be much more likely to improve litter conditions. By the way, in response to your prior post, the bottle bill is definitely NOT good long-term policy – if, that is, the goal is developing our recycling industry and infrastructure to the fullest extent. So I really hope you’re not supporting an expanded bottle bill simply because someone you don’t like/trust is opposing it. We can do better than that.

Fact: states with bottle bills have higher recycling rates than those without.

Fact: states with more comprehensive bottle bills have higher recycling rates than those with less comprehensive bottle bills.

So, if your goal is “developing our recycling industry and infrastructure to the fullest extent,” then shouldn’t you be in favor of policy that results in more recycling. Or, to put another way, what the hell do you think happens to all the empties once they’re returned to the store? Hint: they’re recycled, and by the very industry your post suggests that we should be supporting!

The goal should most certainly be “developing our recycling industry and infrastructure to the fullest extent.” I’m glad there is agreement here. Otherwise, the argument you make isn’t pro-bottle bill, but rather is against taking up the policies of states without the bottle bill

Yes, states with bottle bills have higher recycling than non-bottle bill states, but by no means does this make it good policy. With the exception of Iowa and Michigan, these states are all solidly left leaning (CA, CT, HI, ME, MA, NY, OR, VT). What is really being described here is the relationship of ten states to an abysmal mean, dragged down by a number of states without respectable recycling programs. The far more accurate comparison would be states MA to states with expanded bottle bills, and expanded bottle bill states vs. states with alternative/comprehensive recycling programs.

Connecticut expanded its bottle deposit law to cover non-carbonated beverages in 2008/09 session. Four years later they released a report (pdf link at the top), entitled “Report of the Modernizing Recycling Working Group.” On page 12 the working group cites collection costs brought on by “system fragmentation” as the highest cost, and recommends “less fragmented” collection as the best way to be cost-effective. In the recommendations portion, it is clear the working group is less than impressed by the bottle deposit law, even the expanded version. Their recs for the bottle bill hinge on significant expansion to all beverage containers and raising the deposit to $0.10. The other recommended option is to eliminate the law completely in favor of a comprehensive, “producer responsibility” measures. And this is even more apparent when examining the potential the law has to increase recycling in CT. The charts on pg 15 perfectly illustrate the law’s minimal contributions to overall recycling- AND THIS IS AFTER EXPANSION.

Compare that to Delaware, who switched from a bottle bill program to statewide curbside which was implemented in 2011. From their most recent report, based on information with less than a full year of data, they are having enormous success with increasing their total percentage of MSW recycled, minute portions covered by the bottle bill. From page 8 of the report found at http://www.delaware.gov/topics/recycling – “From 2010 (the year prior to the enactment of Universal Recycling) to 2012 the tonnage of diverted recyclables has increased by over 13%. This increase was largely due to increased yard waste and single-stream recycling. The Connecticut report strongly stresses the need for “dramatic changes” to reach its goal of 58% recycling, while Delaware is far closer to reaching their goal of 50% because their major recycling initiative doesn’t focus on a negligible portion of the overall waste stream.

Beyond the more than uninspiring performance of Connecticut’s expansion, there are several logical issues that make difficult for me to support expansion. It is simply not cost effective for most people to save and bring back empty bottles to the store. Even if you are returning to the store, the opportunity cost of storing large, cumbersome boxes/bags and the time required to actually redeem is ridiculous compared to the recouped amount. Also, funding for the Clean Environment Fund through unclaimed deposits means the state benefits when people don’t recycle. If the goal is to build the recycling infrastructure, I cannot support a policy in which the funding of recycling programs is reliant on the failure of people to recycle.

This is pretty confusing:

So, they are so unimpressed with an expanded deposit law that they recommend either expanding the deposit law or eliminating the existing law. You’re going to have to explain that a little better.

This quote doesn’t support your argument:

You do know what single-stream recycling means, don’t you? it means that the resident doesn’t have to sort papers, plastics, and glass into separate piles; they get picked up all mixed together. Single-stream increases recycling because it’s more convenient for the resident. Neither single-stream nor yard waste have anything to do with bottle deposits. I would like to see what Delaware’s experience with bottle litter is before and after ending their deposit law. As has been pointed out several times here, litterbugs don’t recycle.