(Cross-posted from The COFAR Blog)

A COFAR Special Report

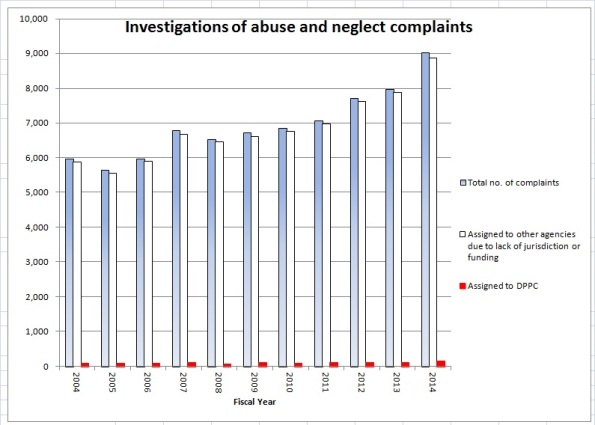

Due to a chronic lack of funding and a maze of legal constraints, the state’s only independent agency charged with investigating abuse and neglect of disabled individuals is able to undertake less than 2 percent of such probes, according to data reviewed by COFAR.

The Disabled Persons Protection Commission’s data show that between fiscal years 2004 and 2014, the agency investigated an average of 101 cases each year, or 1.5 percent of the average number of abuse and neglect complaints investigated.

An average of 6,836 cases per year – or more than 98.5 percent of them – were assigned or referred to other agencies to investigate, with the Department of Developmental Services chief among them.

Source: DPPC

“The DPPC may have one of the most important missions of any agency in state government,” said COFAR Executive Director Colleen Lutkevich. “Yet, it is barely permitted to operate. It’s a shameful situation.”

The impact of the agency’s lack of adequate funding appears to have changed little since The COFAR Voice published an in-depth look at the agency in 2004. At that time, the newsletter noted that between 1999 and 2003, the number of agency personnel investigating abuse and neglect complaints had dropped, due to budget cuts, from seven investigators to three.

A follow-up review by COFAR this year of DPPC reports and budget documents shows that in the decade between fiscal 2004 and 2014, neither the governors involved nor the Legislature demonstrated a consistent commitment to the DPPC or its mission. In a number of years, the agency’s budget was cut, resulting in the need for layoffs of investigators and other personnel, despite rising caseloads.

Among the results of the lack of funding is that the DPPC has been able only to increase its investigative staff from three in 2004 to six currently; and some of those investigators have other duties and are not available to work on investigations full time, according to Emil DeRiggi, deputy executive director of the agency. The investigative staff actually appears to be smaller than it was in 1999, which seven investigators were employed.

The DPPC is the only state agency in Massachusetts whose mission is devoted exclusively to preventing and investigating abuse and neglect of disabled persons. Other agencies that undertake those investigations also employ or fund caregivers who provide a wide range of services to the same individuals. This appears to cause potential conflicts for those agencies by requiring them to investigate their own services.

According to DeRiggi, the DPPC maintains an oversight responsibility over investigations it assigns to other agencies. However, the DPPC’s lack of funding appears to limit its oversight capacity.

The DPPC’s oversight officers, whose job includes monitoring cases assigned to other agencies, have seen their caseloads rise steadily. As of fiscal 2004, there were seven oversight officers at the agency, according to the annual report for that year. As of fiscal 2014 – a decade later – the number of oversight officers had grown only by one, to eight. Yet the total number of abuse and neglect complaints called in to the DPPC in fiscal 2014 was more than 3,000 higher –or more than 50 percent greater – than the number in fiscal 2004.

Lack of statutory authority

The DPPC’s enabling statute (Massachusetts General Laws chapter 19C) permits the agency only to investigate cases involving victims between the ages of 18 and 59. As the DPPC’s website describes it, the agency “fills the gap” between the Department of Children and Families (which investigates abuse of children through the age of 17) and the Executive Office of Elder Affairs (which investigates abuse of persons over the age of 60).

This situation involving individuals with developmental disabilities is further complicated because the Elderly Affairs agency is prohibited by statute from investigating abuse cases involving elderly persons in long-term care facilities such as developmental centers and group homes. The result is that the Department of Developmental Services has become, by default, the only agency with authority to investigate complaints of abuse or neglect of individuals over the age of 60 with developmental disabilities living in those residential facilities. DDS, however, faces a conflict of interest because it is frequently in the position of investigating charges of abuse and neglect in facilities either run by its own staff or by contractors it funds.

Perry case illustrates need for an independent investigatory agency

The case of the 2013 death of Dennis Perry, an intellectually disabled man, at the Templeton Developmental Center, illustrates the need for abuse investigations to be conducted by independent agencies such as the DPPC.

Perry, who was 64, died in September 2013 after having been allegedly shoved into the side of a boiler at the developmental center’s dairy barn by Anthony Remillard, a resident of the center, who had a history of violent behavior. As COFAR noted in a blog post, the DPPC was prevented by statute from investigating Perry’s death because he was over 60. The Executive Office of Elder Affairs was similarly prevented from investigating the matter because it occurred in a long-term DDS care facility. The investigation, as a result, fell by default to DDS.

The DDS investigation report raised a number of questions about its thoroughness. The report and related correspondence, dated in August 2014, concluded that there was no evidence that the staff at the Templeton Center could have prevented Remillard’s alleged “spontaneous and unpredictable assault” on Perry.

The DDS report, however, appeared to have failed to address a number of key questions about the Perry case, including whether it was appropriate for Remillard to have been admitted to the Templeton Center in the first place, and whether the overall level of supervision at the Center or of Remillard himself was adequate. The report merely examined the actions of staff caring for Remillard in the moments prior to, and during, the alleged assault.

Recognizing the need for independence in investigating the abuse of all persons in DDS facilities, the DPPC proposed legislation as long ago as 1992 that would have allowed it to investigate reports of abuse of elderly persons living in facilities operated or contracted by DDS. However, neither that bill nor similar bills filed in the following two years were enacted. The DPPC tried again in 2000, but that bill failed as well, and the agency hasn’t tried again since, according to DeRiggi.

Lutkevich does not believe legislation to give the DPPC more statutory authority to investigate a wider range of cases would have failed to gain passage in the Legislature had there not been behind-the-scenes opposition to it. That opposition, she maintains, has most likely come from DDS, the agency with the most political turf to protect in matters regarding abuse and neglect investigations.

“If DDS had wanted those bills to go forward (to give the DPPC more investigative authority), they would have,” Lutkevich contended.

A critical mission thwarted by underfunding

COFAR President Thomas Frain similarly said he believes DDS is largely responsible for keeping the DPPC in a state of perpetual underfunding in order to prevent it from having the fiscal resources to investigate more cases in the DDS system.

“DDS has enormous influence and sway over the Legislature,” Frain maintained. “Historically, the Legislature has not gone against DDS. If DDS was in favor of adequate funding for the DPPC, its funding situation would improve overnight.”

As the DPPC’s website notes, the agency’s mission is “[t]o protect adults with disabilities from the abusive acts or omissions of their caregivers through investigation oversight, public awareness and prevention.” The DPPC also arranges for protective services when abuse has been substantiated and provides training and education for service providers, law enforcement agencies and others.

As noted, however, the DPPC’s funding level leaves it unable to carry out its mission fully or effectively fill the gap between the Children and Families and Elder Affairs agencies.

Budget woes have affected staffing

As of fiscal 2014, the staff of the DPPC included four individuals in its administration and finance office, five in its hotline intake unit (with a contracted provider operating the hotline after hours), five in its investigations unit, eight in an oversight unit, two in outreach and prevention, one in information and technology, four in document retention, and two in a legal unit. As noted previously, not all of those staff positions are full-time. That total number of staff was lower in fiscal 2014 than it had been in fiscal 2010.

The DPPC’s budget does not include a five-member Sate Police Detective Unit assigned to the DPPC, which reviews every report to the hotline to determine if a criminal investigation is necessary.

The DPPC’s total funding rose from $2 million to $2.8 million in inflation-adjusted (fiscal 2015) dollars between fiscal 2004 and 2014 – a 37 percent increase over that period. But budget cuts between fiscal 2009 and 2012 necessitated overall staffing reductions, according to agency annual reports and other records. It’s not clear that the agency ever recovered from those reductions.

The agency’s funding level has risen and fallen in the past decade, reflecting the state’s fiscal outlook. In fiscal 2009, funding had actually been increased from the previous year by $204,000, the largest increase the agency was to receive until the current fiscal year. DPPC Executive Director Nancy Alterio stated in the agency’s fiscal 2009 annual report that as a result, DPPC was able to increase its investigation staff by 50 percent, from four to six investigators, “in addition to addressing other caseload challenges in the oversight unit.”

In addition, the number of “overdue” investigations in fiscal 2009 decreased from over 900 to 578, Alterio said. Overdue investigations are those taking more than 30 days to complete. But in the annual report, Alterio also warned that those gains in staffing might be reversed in fiscal 2010.

That warning came true. The DPPC budget was subsequently cut each year from fiscal 2009 through 2012, dropping from $2.6 million to $2.3 million in inflation-adjusted dollars. It was only in the current and past two fiscal years that some of that lost ground was made up in the form of increased funding, bringing the budget to $2.8 million in fiscal 2014.

While fiscal 2009 did mark the beginning of three years straight of budget cuts, the number of overdue investigations did continue to drop to a low of 465 in fiscal 2012, according to DPPC data. But after that, the number of overdue investigations began to rise again, back to more than 600 in fiscal 2014. In fiscal 2010, Alternio noted that about 85 percent of investigations were not completed in 30 days.

In fiscal 2010, the DPPC was forced to reduce its total workforce from 32 to 28 Full Time Equivalent (FTE) staff. Yet at the time, the agency was facing an average annual increase in abuse reports of 4 percent, stretching over the previous 10 years, according to Alterio. Between fiscal 2004 and 2014, an average of 2,100 abuse and neglect complaints a year have been “screened in” by DPPC for investigation.

The DPPC received a relatively small increase in funding in fiscal 2013 of about $86,000, but it was not enough to prevent an additional layoff and reduction in the total staff to 27.4 FTEs.

“Each fiscal year, operating expenses increase and therefore additional funds are necessary just to maintain operations at the same level from year to year,” DeRiggi wrote in response to an emailed question.

A ray of hope in the current fiscal year

The current fiscal year opened last July on a slightly more positive note for the DPPC. For the first time, the agency received a funding increase of more than 10 percent. The Legislature approved a $362,000 increase in agency funding, bringing the DPPC’s budget to $2.8 million.

According to DeRiggi, the budget increase was projected, among other things, to allow a seventh investigator to be hired in the current fiscal year. That 13 percent increase in funding in inflation-adjusted dollars had not been in the budget submitted in January 2014 to the Legislature by former Governor Deval Patrick. Patrick had proposed only a $48,000 increase for the DPPC, which would have been less than two tenths of a percent if adjusted for inflation. It was apparently in the Senate that the larger increase was approved.

Asked if there was a particular legislator who had sought the 13 percent increase for the DPPC, DeRiggi said he and agency staff were not aware of who that might have been. “Hopefully this year’s proposed allocation is a reflection of an understanding of the seriousness of the issues DPPC investigates, but we are not certain of why it came about,” he said.

But given that the outgoing Patrick administration and incoming Baker administration have projected a budget deficit in the current fiscal year that could run higher than $700 million, it is once again possible that the DPPC’s budget will be cut, requiring another cycle of staffing reductions.

And despite the funding increases that the agency received starting in fiscal 2013, it has not been able to restore all of its functions and services that were cut in preceding years. For instance, in April 2009, the DPPC was forced to eliminate a service to human services providers under which it would search its database to see whether prospective employees had been charged with abuse. That service has not since been restored.

(Upcoming post: A case in which the DPPC got sidetracked from its mission)

It is understandable that the funding for agencies such as DPPC fluctuates with the overall state budget, the economy, etc. Unfortunately, the number of cases of reported abuse don’t follow the same pattern. And it just isn’t right that the onus of investigation falls to the Department of Developmental Services when DPPC can’t accommodate the load. I challenge any legislator to justify the practice of any agency being high-minded or impartial enough to investigate serious complaints against personnel and practices which that agency oversees to begin with. Internal investigations just can’t meet the same standards as oversight from the outside.

I agree with your challenge.

Just as a point, its interesting that the number of abuse and neglect complaints have risen, steadily and fairly dramatically, from 2004 to 2014. With particular note of the years from 2010 to a spike in 2014 (a high for the last 10 years). Seems to coincide with DDS

push to close developmental centers and state operated care to moving the majority of the people they serve out into the community.

Just a thought that instantly came to me as I viewed the bar graph above.