If you are a child of the 50’s or 60’s or very early 70’s …..or very late 40’s….you can recall, with emotional exuberance, the “Middle Class”. Today, in 2017, the Middle Class is a fond memory and one that is fading away. Elizabeth Warren spoke on this subject back in 2007, ten years ago, years before she entered politics (and my first encounter with her, an encounter that changed my view of the world) .

In simple terms, the “middle class” is just a class of laborers who can support themselves and their family in a manner that is socially, fashionably equivalent with the majority of others. In contrast, the class of laborers who cannot support themselves and their family in a manner that is socially, fashionably equivalent with the majority of others are called the poor. The middle class goes to Disney World. The poor do not. The middle class retires at 65, moved to Florida and plays golf until they die at a local hospital paid for by their insurance policy. The poor hang on in Central Falls until they die of pneumonia, on Medicaid. In BOTH case, the citizens involved all worked, a minimum of 40 hour a week, 50 weeks a year. The only difference was in their wages.

Our middle class is dying. We’re not even keeping up with the Canadians.

My hypothesis is this: our middle class is dying because it has allowed itself to separated from the working class and reduce its numbers in the same way that the poor have been suffering because they have been jettisoned by the middle class and become a minority. It is time, hell, it is past time to join these two classes back into one, as the “Working Class”.

In short, if you accept the paradigm of “Middle Class”, you embrace the notion of lower class or poor. You can’t have a middle without two ends. We know we have a wealthy class, the 1%, more accurately the .1%. do we really increase our political power if we fragment the remaining 99.9% in two, fighting each other?

As we look at Donald Trump and his cabinet, it ought to be clear to all of us, from cardiologists to car sales reps to custodians, that it is ALL of us against ALL of them, We cannot win if we divide our ranks by occupation, earnings, (or sex or religion or skin color or language).

Working Class has to be our focus. Middle Class is accepting their paradigm, and one that divides us, isolates us, weakens us.

I challenge all Democratic office holders and those running for office in the years to come to drop the term “middle class” and embrace “Working Class” as our shield.

There were the rich, the desperately poor, and the middle class. We were in the huge middle, and so were most people I knew until I went to college and encountered a broader spectrum. My father was an immigrant lacking a college education. Yet he worked 6 days a week and could afford to buy a house in a rising suburb, support a wife who stayed at home with their children, and send both daughters to excellent public schools and eventually to college. One day, in a discussion with a friend, I learned that my father was not middle class, but rather he was “working class,” a term that made no sense to me. Didn’t EVERY adult work? “Blue Collar” also made no sense. As a Maitre D’, my father was the only man I knew who wore formal clothes to work and had regular manicures. And yet his earnings were virtually minimum wage, and tips the bulk of his income. “Rich” people were the ones who had 4-bedroom houses (we had 3). “Rich” people went away for skiing vacations. “Rich” people had a second home at the shore (we took day trips). I, in fact, did not know anyone who was truly rich–and very few people who were truly poor. Today, Elizabeth Warren and others talk about “working families” and perhaps that is more resonant than “working class.” Your point is that it is “working” that defines us, whether we are custodians or barristas or college professors or software engineers or physicians or day laborers. I agree. Bottom line, we need to define our terms. “Middle class” used to identify everyone who was not truly rich, but knew where their next meal was coming from. Many people probably still think of it that way.

When I think working class, I think wage earners, often those who mostly do physical or manual labor, and usually make in the lower half of five figures per annum. When I think middle class, I think more along the lines of brain work, white-collar, professions, salaried to the tune of high five figures and possibly low six per annum. I do not believe it is accurate to drop one term in favor of the other, but neither is it appropriate to pit the two against each other.

In 1970, the average adjusted for inflation income of general practitioners was $185,000. By 2010, it had fallen to $161,000 despite a nearly doubling of patients doctors see per day. I see it in my own doctor. He’s overworked, just as I was before I was terminated from an awful job. I was in the first group you mention and he in the other, but we shared the same frustration.

As I mentioned in an earlier post, workers at an appliance factory in Kentucky just agreed to a contract between their union and the factory owners that pays them $12 an hour. That’s not even $25K a year. How does a nation support itself on that?

We need to join together and fight for justice.

I think a lot of things here get muddled by the way these things are talked about and perceived.

One important prism is less the idea of “class” as status checkmarks as a lot of what you’re talking are (definitely a class measure), but more what are the actually middle income people are – the actual middle not the perceived “allocation of status markers middle.” Their numbers have not only declined but the whole prism of what those incomes are is so mis-aligned from the that status they can afford by the fact the upper 1% (and even upper 10%) have seen increasing percentage of the gains.

A lot of people are taking on increasing debt trying to obtain what they are being told/sold and believe are the appropriate status items as members of the middle class, but the incomes don’t remotely match the ability to pay (combination of disproportionate inflations are a big part like housing and health care as well as decline of real income in general.)

In terms of incomes, what we have now as incomes able to support a lot of those things really are part of or at least closer to the upper 10% incomes rather than the just the middle incomes in a lot of places especially. And the bigger percentage of actual income middle is becoming even closer to the working poor side in terms of what is affordable.

Which makes the focus on the middle class by politicians often so surreal to me. It doesn’t seem connected to the middle incomes or the lower parts of the “middle class” instead just pretty much ignoring them and the working poor. But more a code word for the ‘professional classes”/upper percents %10 – 3% say.

Just my own insane .02 rambling though…

where they asked people what they thought the wealth distribution was, what they thought it should be, and what it actually is?

Exactly. One of the things I was thinking of.

Also another point that was floating around in resonance with your post is the notion I’ve had for years that one of the key power shifts was how TPTB (especially on the right) have over the decades sold working middle income folks the notion that instead of being people who need/want government protections for those below them in case they move down the ladder; but instead encouraged them to think of themselves as they might be upperclass some day. (Heck, all modern lottery are slaved to that notion!)

Thus segments of them voted against what would be in their best interests and often voted with the interests of those above them (so to speak) rather than those below them as they used to. Like, for a minor example, voting against estate taxes even though that has not impact on them nor ever likely to and voting against worker protections that probably do and are more likely to someday than the former.

And while I’m babbling. 🙂 I think a lot how much the notion that shift is also impacted from the generational shift from a generation that saw the previous generation’s classes sudden losses (Great Depression) versus the more contemporary ones who saw the previous one’s uplift (immediate Post WW II era.)

Just a thought or two or three.

The biggest problem the world is facing right now is that one of the fundamental, unquestioned axioms of economics is starting to fail- the idea that demand is substantially larger than supply. As productivity rises, average lifestyles have to increase by the same amount to maintain full employment. 200 years ago, the majority of people in the world were farmers. Now only a small percentage of the country is involved in farming. We managed to occupy everyone else building cars, televisions, and computers. But we are already reaching the point where an average person working for their entire life will produce more than what most people want to consume. To some degree, this can be solved by becoming more wasteful – replacing a television every year requires more productive output than replacing it every five years. But as manufacturing becomes more automated, even increased consumption won’t be able to keep up with what full-time work can produce.

As productivity continues to rise, employment rates are going to keep dropping. As long as we maintain our current economic structures, this is going to be done by having a higher unemployment rate and a growing class of poor people. It is the ultimate irony that the result of people becoming too productive and producing more than they can consume is that more and more people will not be able to maintain a reasonable lifestyle.

If we accept that employment rates are going to drop, we have basically three options: reduce the retirement age, increase standard vacations/shorten the work week, or have growing unemployment. This is the real problem with framing the discussion as being about the working class. We should be trying to change our economic structures to reduce average employment in a more reasonable way. We should be trying to reduce how much time people spend working. We should be pointing the way towards a future in which people only work for a small portion of their lives. We should be trying to remove people from the working class while maintaining their middle class lifestyles.

The next twenty years are going to bring about more change than the past 100 years have. 20 years from now, most people will have a 3d printer in their house that can make anything they ask for, electricity will be too cheap to meter (between solar, wind, and fusion), and cars will drive themselves. We won’t have a manufacturing industry, because almost everything will be made at home, without labor. We won’t have a transportation industry, because that will be done entirely by robots. We won’t have a large financial industry because deflation will drive prices so low that people won’t bother with money. The working class is dying, and that needs to be made a good thing.

I’m not so sure. Since 1975, the average size of a new single family home has grown from 1600 sq ft to 2600 sq ft.

That’s 63% more space to construct, to heat and cool, and to furnish. Not only are we buying appliances more frequently, but they’re far bigger than they used to be.

Americans consume more and more every year — we consume more, we consume bigger, and we consume higher quality.

Interesting anecdote here and a pro-tip on savings. Much of home’s furniture was old, broken, not matching. I decided to go on line, Freecycle, Craigslist, etc. What I was able to buy was astounding. Ethan Allen and Thomasville tables for pennies on dollar. All from very ritzy homes who were simply “redecorating”. Last week, my dishwasher died. Back to the Internet and I discovered dozens of sellers looking to unload virtually new ones for 1/3 the cost of new. Why? Well, they just remodeled their kitchen. Of course, nothing was wrong with the old one, it was just out of style. And there is this: The average American spends less that 30 minutes a day cooking in their kitchen.

In some aspects I agree, I will throw a caveat out about “higher quality” I find a huge number of goods simply no where as well made nor long lasting as they used to be. Which tends to add an amount a replacement spending for some folks that didn’t used to be there.

Just a thought…

But that actually kind of proves my point. With a lower average level of employment, we are building bigger houses and putting more into them. But at some point, people won’t keep wanting bigger houses. Do you think that the average house size is going to increase to 3600 sq ft by 2053? Do you think that would actually make most people happier? Given the exponential increase in productivity over time, we would probably have to increase the average house size even faster going forward to maintain full employment. We would probably need to get above 6000 sq ft by 2050. If household size continues to decline, are people really going to want that much space and stuff? At some point, people are going to decide they would rather retire at age 40 and live in a smaller house. It takes a lot of consumerist advertising to keep the spending rate increasing fast enough to maintain full employment, and I’m not sure how much longer we can manage to keep that going.

Reasonable expectations of productivity gains suggest that in 20 years, we will need about 1% of the population in farming, about 1% in manufacturing, and about 1% in construction. That 3% of the population will be able to produce everything that we use and consume. What will everyone else be doing? We can have a bunch of lawyers and bankers making sure that everybody only has the goods they have earned. We will probably still have people employed in health care, although robots can handle many of the more mundane tasks such as dispensing drugs. We will have entertainers of various sorts. But how can you actually create work for about 50% of the population?

Whose reasonable expectations? America has 6.671M construction workers out of 145.303M jobs. That’s 4.6%. And you think that falls to 1% in 20 years?

Just making up numbers does nothing to further the conversation.

First of all, I said 1% of the population, not 1% of jobs, so construction is at about 2% right now. For reference, the employment-population ratio is typically around 60%. I expect that number to decline substantially, which is why I am using the population ratios.

We have all the technology we need now to 3d print entire buildings. It isn’t yet developed far enough to actually do so, but it would be unreasonable to expect construction to continue being labor intensive for much longer. At some point in the next decade, someone is going to put up a building with almost no construction workers involved. Within twenty years, that is likely to be considered standard practice.

Manufacturing output per hour of labor has tripled over the past thirty years, and we now have manufacturing employment at about 3.5% of the population. And productivity stalled after the 2008 recession, so productivity had basically tripled in 20 years. Assuming that technology was still improving, we should be able to quickly incorporate what should have been another 50-70% increase in productivity over the past ten years once demand increases enough. This means that just extrapolating past productivity trends leads to sub 1% employment in manufacturing in 20 years if output is approximately the same as it is now. Additive manufacturing has the potential to increase productivity at a much faster rate then anything we have seen in the past. The 1% number is almost certainly too high.

And farming is already at just 1% of the population, down from 2% in the late 80’s. That number will probably also drop further.

If you want to be pessimistic about technological advances, then you could say that I am off by 10-20 years. That still means that by the middle of this century, it will be nearly impossible to maintain anything close to full employment. This isn’t a problem in the distant future, this is a problem that we will have to deal with by the time that babies being born now are entering the workforce, or at most by the time they are middle-aged.

A more effective counter argument would be that those three industries are currently only about 7% of the population, so dropping that down to 2% in total isn’t really that big of a change. But that would still roughly triple the unemployment rate to about 15% (of people interested in working). And if people are forced to compete with lower wages for the jobs that are still available, it will cause an unending recession driving demand down, reducing employment even further.

As one example of how 3d printing will destroy manufacturing jobs: we know how to 3d print rockets. A rocket engine is fairly sophisticated, has several moving parts, and has tight tolerances. Any manufacturing technology that can produce rocket engines can basically make any kind of machinery. 3d printing of electronics is also getting started. Once additive manufacturing matures a bit more, there will be machines that can make anything you have the design for in just a few hours, all unsupervised.

And here is one about 3d printing a house. Not labor free yet, but again, the technology is still new. 20 years is a long time and a lot of progress will be made.

In another 10-15 years, people will be able to buy a device that fits in their house and can produce virtually anything they might want. Current prices for 3d printers are around $200 for one that can print with only one material and going up to a few tens of thousands of dollars for ones that can print multiple materials (plastic, wood, metal, ceramics, and electronics) at high speeds. And people are also working on how to recycle the printed objects back into the raw materials to be used again. We can do it now if you don’t care about color.

And the houses themselves will be printed by larger printers in a couple of weeks. Why remodel part of a house when it will cost less to recycle/reprint it into a completely different design?

In a world where every house has a 3d printer, how do you maintain full employment?

…Have been made for centuries. Regardless of whether the numbers are sound (see stomv comment prior) the arguments are similar and, essentially, zero sum. 100 years ago we paid small sums to a large number of longshoremen to load and unload boats. Now we pay larger sums to a smaller number of people to load and unload containers and truckers to take them to and fro. The job “longshoreman” went away, but manufacturing of containers, loaders, ships and trucks increased and training jobs for trained personnel also increased. The game is not zero sum, it is, in fact, positive sum.

Whatever the present level of construction jobs now is likely to be the same, if not increase, in 20 years because things we build break down especially if productivity is on the increase now… The level of manufacturing jobs will likely stay the same, if not increase, because when robots make things somebody will have to make, maintain, program and repair the robots. While we can farm more with less personnel, more agricultural product increases the jobs in transportation and distribution and if, as somebody mention previously, people don’t use their kitchens more than 30 minutes a week, then that increases the jobs in the restaurant and food-service sectors…

The Malthusian argument is that we won’t have enough resources to produce everything we need to survive. My argument is the exact opposite, that we won’t have enough demand to consume everything we produce. The Malthusian problem can be solved by limiting population growth, while the problem I am pointing out is unaffected by population size because it is about average production and consumption per person. I’m not sure why you are bringing up Malthus. In a zero-sum world, these problems can’t ever come up because output can’t increase faster than population.

There will be essentially no jobs in transportation in twenty years (or at least no jobs operating vehicles). Self-driving cars now are about as safe as human drivers, and the technology is still brand new. Insurance considerations are likely to push people to stop operating personal vehicles in 10-15 years, and fleet vehicles will stop even faster.

The number of people making/fixing/operating robots to manufacture things will always be smaller than the number of people that would be required to make the same output without the robots, and often by a rather wide margin.

We also have the technology now to make automated restaurants. I’m not sure how popular they will be, but we can custom-make food to order from something that is equivalent to a large vending machine. I wouldn’t count on restaurant employment to provide job growth going forward.

Elizabeth Warren addressed this change, last year.

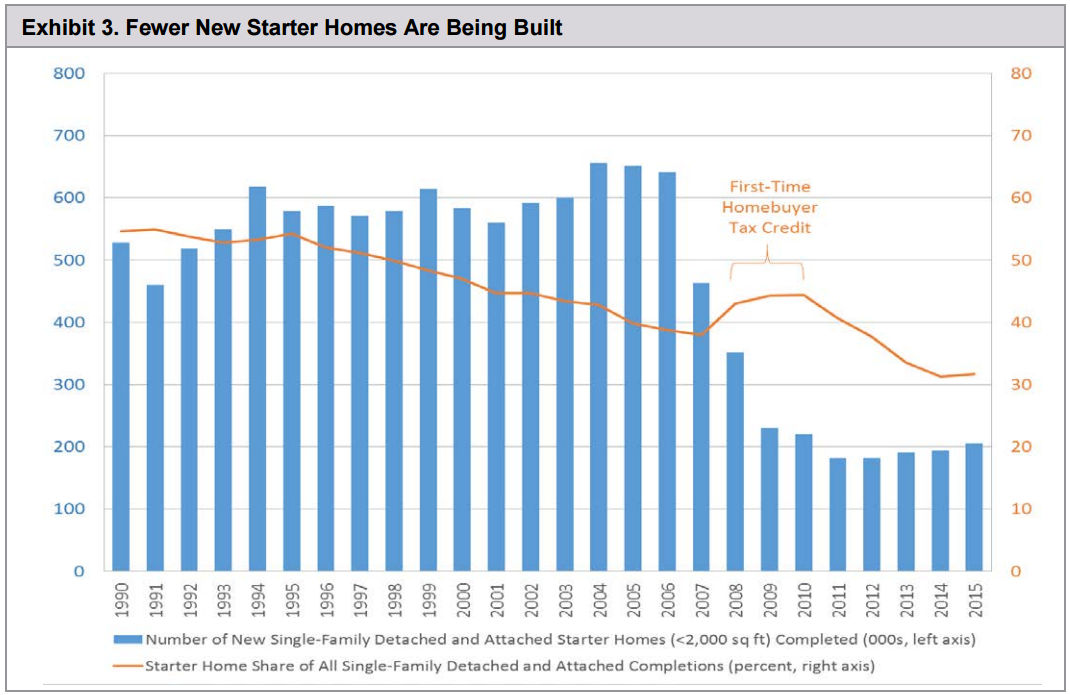

The rate of household formation has plummeted since the Great Recession, and has been declining during period of this chart. That means that young people who can’t get work, have staggering student debt, and can’t afford any sort of housing are moving back in with their parents instead of going out on their own.

That, in turn, means that young people aren’t buying houses now. That, in turn, means that new houses aren’t “starter” homes any more. The housing market, today, is dominated by older people and by investors.

This is a good example of how the crisis in student debt ripples through the rest of the economy.

We see a massive new housing start drop off at W’s recession. But total starts a year ago were back within the envelope of where they’ve been since 1966. The December 2016 number was 1.226M, even higher than the green line has reached in the chart above.

So it may well be that today’s young people aren’t buying the new homes — that they’re buying the homes vacated by older people and investors. But is that really different than 40 years ago? Were newly-wedded 24 year olds buying new homes back then, or were more established couples buying those while the young couples were buying the houses those more established families were vacating? Data please, not anecdotes…

And, of course, regardless of who is buying the homes, the fact remains that the average size of a home in America continues to grow, and that means the number of couches, televisions, picture frames, and area rugs, to say nothing of 2x4s, gallons of paint, and boxes of flooring purchased continue to increase too.

Editors should feel free to change the width to something reasonable, like 600 px. My browser “helpfully” did that when I previewed, so I didn’t realize the size.

Apologies!

Here’s one relevant paper (from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco), I’m still looking for the piece I heard (I think it was Ms. Warren, perhaps on NPR).

I found “1st-Time Buyers, single woman rise in housing market“, from last October (emphasis mine):

I’m still looking for the data about the extent to which housing starts have been targeted towards first-time buyers. I know I’ve seen that, but it’s harder to find. Google has a rather strong bias towards recently-published work, so looking at past data is harder (at least for me).

I found “Starter Home Drought Leaves First Time Buyers Thirsty, from October of 2016 (emphasis original).

There’s also this interesting graph:

Editors: It seems that the “width” attribute on img tags is being ignored

Supports the elimination of the mortgage deduction. Any true progressive would as well.

Effectively this is a gift for the upper middle class and upper class. Of course realtors are against it, as removing it should result in lower prices for real estate.

I can only speak for my wife and myself, but we are six years out of school and only now have a healthy enough debt-income ratio to begin saving the 20% you’re supposed to put away from your paycheck. We are hoping to eventually hit 30% so we can save up for the apartment ‘down payment’ the Boston area typically requires (first, last and deposit).

Granted, I’ve switched jobs more frequently than she has and have about five months of total unemployment in between jobs for those last six years, and she’s paying as she goes for community college now, but our experiences aren’t entirely atypical. Friends back in Cambridge with JD’s and MA’s are living with their folks. A few friends share my situation of crashing with parents or spouses parents (I’ve done both this year) and having to help pay the rent or mortgage for their folks . Being middle class in Boston is wicked expensive.

My Anecdote…1973 (the year is all ended for the working class)

Graduated from high school with a less than stellar C+ average. Applied for an entry level job at Xerox, Bausch & Lomb, Stromberg Carlson. Was offered a job at all three, accepted a job at Xerox, entry level, day and evening swing shits (no graveyard) for about $45K a year, adjusted for inflation. (plus full medical, vacation pay, full benefits)

Lived at home and saved enough to buy a new car and save for my next two years of college, leaving Xerox after 12 months. Community college was about $7,000 a year (adjusted for inflation) and two years at a private university was about $15,000 per year. Took out a loan and paid it off in five years.

My first job out of college paid (inflation adjusted), $60,000 a year, plus a car and all car related expenses 1979. Bought a house in 1980 for $200K (inflation adjusted).

For the working class, America was Great in 1973.

I had no idea how good I had it or that it was never going to happen again.

That’s going to haunt me…

Republicans take the position that we need to work more, not less, by raising the age of social security eligibility and erasing laws regulating overtime pay. Some Democrats take the position that the surplus unemployed just need new skills. As you point out, both are invalid solutions as both ignore the cause of unemployment: we have a surplus of labor. Combine that with a Puritan Work ethic and here we are.

Love the line “The working class is dying, and that needs to be made a good thing.” Personally, in my adult life I have never enjoyed going to work until just recently. Mind you, I worked since I was 16, put myself through college, worked nights, weekends, and have enough variation in my past jobs to make a movie staring Tom Hanks (that guy can play any role!). I never understood the idea that everyone needs a career. I never wanted one. I just worked to make money. I was happiest when not at work. I think a majority of people are that way. Sure, there are a few who are happiest at work. Painters, sculptors, musicians, some doctors and scientists, athletes, you get the picture. I’m there now. I work 20-30 hours as a produce clerk in a food market. As a “foodie”, I am in my element. As someone who gets joy from helping others, I get to do so all day long.

Of course, financially I could never do this without my previous hours on “the job”, but at 62, I’ll take it.

I wish we could all enjoy life this way. I wish I could have done this sooner.

It is entirely possible.

N/T

…a little late. Prior to election day, Chuck Schumer predicted: “for every blue-collar Democrat we lose in Pennsylvania, we will pick up two moderate Republicans in the suburbs in Philadelphia, and you can repeat that in Ohio and Illinois and Wisconsin.”

And he’s now the senate minority leader……..and it seems many here on BMG agree with him still…..