China Telecom’s Internet Traffic Misdirection

A potentially major cyberwarfare story broke yesterday in the midst of the usual din of Trumpist outrage (emphasis mine):

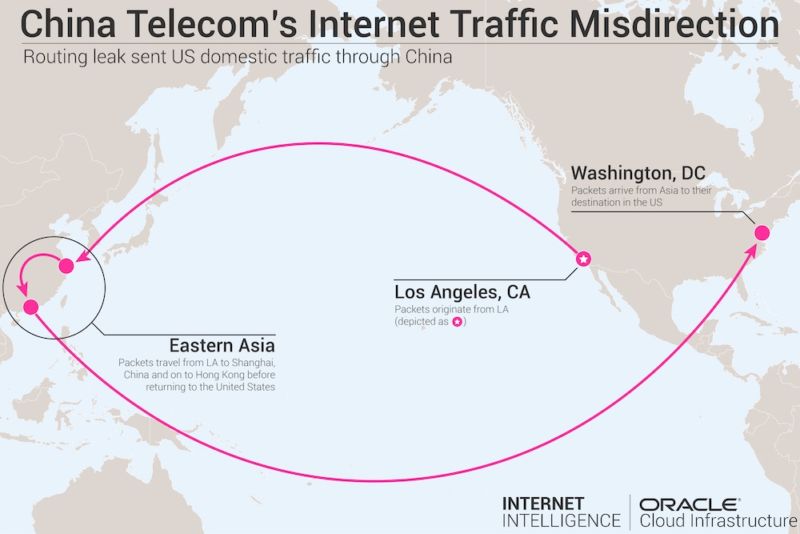

China Telecom, the large international communications carrier with close ties to the Chinese government, misdirected big chunks of Internet traffic through a roundabout path that threatened the security and integrity of data passing between various providers’ backbones for two and a half years, a security expert said Monday. It remained unclear if the highly circuitous paths were intentional hijackings of the Internet’s Border Gateway Protocol or were caused by accidental mishandling.

For almost a week late last year, the improper routing caused some US domestic Internet communications to be diverted to mainland China before reaching their intended destination, Doug Madory, a researcher specializing in the security of the Internet’s global BGP routing system, told Ars.

…

The routing snafu involving domestic US Internet traffic coincided with a larger misdirection that started in late 2015 and lasted for about two and a half years, Madory said in a blog post published Monday.

…

By routing traffic through networks controlled by the attacker, BGP manipulation allows the adversary to monitor, corrupt, or modify any data that’s not encrypted. Even when data is encrypted, attacks with names such as DROWN or Logjam have raised the specter that some of the encrypted data may have been decrypted. Even when encryption can’t be defeated, attackers can sometimes trick targets into dropping their defenses, as the BGP hijacking against MyEtherWallet.com did.Madory said the improper routing he reported finally stopped after he “expended a great deal of effort to stop it in 2017.” His report on Monday went on to endorse a proposed standard known as RPKI-based AS path verification. The mechanism, had it been deployed, would have stopped some of the events Madory documented, he said.

…

Monday’s blog post comes two weeks after researchers at the US Naval War College and Tel Aviv University published a report that quickly got the attention of BGP security professionals. Titled China’s Maxim–Leave No Access Point Unexploited: The Hidden Story of China Telecom’s BGP Hijacking, it claimed the Chinese government has brazenly used China Telecom for years to divert huge amounts of traffic to China-controlled networks before it’s ultimately delivered to its final destination. The report named four specific routes—Canada to South Korea, US to Italy, Scandinavia to Japan, and Italy to Thailand—that were reportedly manipulated between 2015 and 2017 as a result of BGP activities of China Telecom.

I apologize for the lengthy quotes — it can be challenging to appreciate the impact of this attack.

The bottom line is that this is strong evidence that a significant portion of the traffic to and from Washington DC was directed through mainland China, where that traffic is vulnerable to malware hosted on Chinese hardware operating under Chinese government supervision on the Chinese mainland.

The story has not yet been picked up by any mainstream news sources that I know of. There is precious little air for anything except politics at the moment.

If this report turns out to have substance (it is still unfolding), this will or should be a major news event. It is the cyberwarfare analog to the attack on Pearl Harbor.

OK, I’m pretty dense when it comes to this stuff. What is the impact of this on average Joe’s internet usage?

Perhaps not too much, because it isn’t clear that the average Joe was the target.

If you were an average Joe living in the Washington DC area, it meant that about 20% of the information you sent and received via the internet was routed through servers that have a history of misusing the data that comes through them — harvesting and selling credit card and bank account information, for example.

The more likely targets were the tens of thousands of low- and mid-level political, governmental, and even military staffers, interns, and family members who live in the DC area. Email addresses, contact lists, and of course credentials for secure systems are the kinds of things that foreign agents are interested in.